Archive for the ‘World War II’ tag

Veterans Day

These week we celebrated Veterans Day in the United States to honor those who have served the country and those who are still serving. As we remember our living veterans let us not forget those who are no longer with us. As a poet once said: “All gave some, but some gave all.” You can find information about the various military cemeteries in Normandy, France by linking to them from the links provided on this site. If you link to the American Cemetery, here is some of what you will find:

The Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial in France is located on the site of the temporary American St. Laurent Cemetery, established by the U.S. First Army on June 8, 1944 and the first American cemetery on European soil in World War II. The cemetery site, at the north end of its ½ mile access road, covers 172.5 acres and contains the graves of 9,387 of our military dead, most of whom lost their lives in the D-Day landings and ensuing operations. On the Walls of the Missing in a semicircular garden on the east side of the memorial are inscribed 1,557 names. Rosettes mark the names of those since recovered and identified.

The memorial consists of a semicircular colonnade with a loggia at each end containing large maps and narratives of the military operations; at the center is the bronze statue, “Spirit of American Youth.” An orientation table overlooking the beach depicts the landings in Normandy. Facing west at the memorial, one sees in the foreground the reflecting pool; beyond is the burial area with a circular chapel and, at the far end, granite statues representing the U.S. and France.

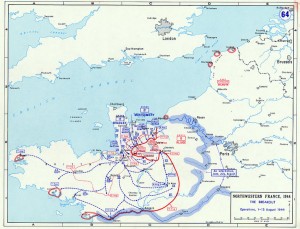

The Normandy Campaign Draws to an End

Sixty-five years ago this month, the Normandy Campaign was coming to an end after almost ninety days of brutal combat between the Allied armies and the German Wehrmacht. It began on June 6th, D-Day when British and American paratroopers jumped into the Cotiten Peninsula to secure key terrain and disrupt the Germans in advance of the assault divisions that landed on five beaches stretching for fifty miles along the coast of Northern France. Their mission was to secure a lodgement, destroy the German forces, and liberate Europe from Nazi tyranny. Although there was bitter fighting right from the start of the invasion, it only grew more intense over the next few months as they fought in the Bocage of the peninsula which was a patchwork of hedgerows. The hedgerows provided a natural defensive position from which the Germans could effectively blunt any Allied advance, and they successfully used machine guns and artillery to great advantage. Despite the Allied advantage in air power and naval gunfire , the Germans put up a stiff resistance. Their army was well trained, had combat experience, and many units, specifically the SS, were fanatical fighters who were dedicated to the Nazi regime.

Over the next few months, Allied commanders launched a series of attacks and utilized their superior air and naval forces to prepare the advance. Tragically, there were many occasions where incidents of friendly fire took place as bombs fell short of their intended targets, and Allied soldiers were killed or wounded even before the operations commenced. Yet they remained fixed on their mission, and demonstrated resilience to continue to pursue the Germans relentlessly. Resilience was crucial to the success for the Allies. It is the simple quality of an organization or individuals to overcome setbacks, and spring back so they can move ahead towards their intended objectives. Time after time, Allied soldiers and their commanders were able to overcome significant losses and rebound in spite of them.

As the weeks past, the Allies continued to bring more men and equipment into the fight while the Germans could not replace their losses. Among the German losses were some senior commanders, include Field Marshal Rommel. He was seriously injured when his staff car was attacked by an Allied fighter plane while he was traveling to visit the units at the front lines of the battle. Visiting the front at the crucial points was his custom and one of the reasons why he was one of the most effective German commanders. As the German losses mounted, their ability to counter attack was diminished. Nevertheless, Hitler demanded more aggressive action from the safety of his headquarters in East Prussia. In frustration, Hitler replaced his Commander-in-Chief, Field Marshal von Rundstedt, with Field Marshall von Kluge. When he arrived in Normandy, Kluge originally thought that the biggest problem for the Germans was a lack of leadership, but as he visited the front lines, he too quickly realized that the German army simply was not able to withstand the onslaught without more replacements and support. On July 20th, an attempt was made on Hitler’s life when a bomb was set off in his bunker in East Prussia, but he sustained only minor injuries. Although his injuries were only minor, he was ruthless in pursuing the perpetrators which included a number of regular army officers. Kluge was concerned about being implicated in the plot, so when Hitler ordered a major counter attack against the Americans from the German left flank, Kluge reluctantly carried out the order even though he knew it was the wrong strategy from purely a military standpoint. This attack at Mortain only played into the Allied plan as it was held in check while the newly activated American Third Army under General Patton broke out of the hedgerow country with his armored and mechanized formations to envelop the flank of the German Army. Within a matter of days, the German attack was completely contained, and the Americans were able to advance almost unopposed into the German rear areas.

Patton drove his troops relentlessly to continue their attack so that the Germans would not have time to recover. This was exactly the right strategy. He exploited success and when necessary even by-passed pockets of resistance to keep up the momentum. By mid-August many of the German units were depleted and beginning to break down under the stress of constant combat. After encircling most of the German Army, the Americans and British attempted to complete the encirclement at Falaise. The Canadians and Poles were attacking from the north towards Falaise while Patton’s Americans and the French 2nd Armored Division were attacking north intending to meet up with them. After reaching Argentan, Patton was ordered to stop his advance to avoid a friendly fire incident with the Canadians and Poles; however, the Canadians and Poles had run into determined resistance from SS Panzer units that were trying to keep the Gap open so that others could escape east across the Seine River to fight another day. In this, they were successful for awhile, but eventually the gap was closed and the Allied air forces relentlessly attacked any Germans on the road moving east. By the end of August, the remaining Germans who were not killed inside the “Falise Pocket” surrendered to the Allies. Knowing that he would be blamed for the defeat, Kluge took his life with a cyinad pill. Meanwhile, the German commander in Paris defied Hitler’s orders to destroy the city and defend it to the last man. He declared it an “open city” and so it was fortunately spared the fate of many of the smaller villages and cites in Normandy that were ruined during the preceding weeks of brutal combat. The Free French Forces under the command of General LeClerc were given the honor to be the first Allied troops to enter Paris.

With the liberation of Paris, the Normandy campaign was officially over, but price in terms of casualties and destruction of property had been great. Not just for the armies, but also for the many French civilians who were killed, wounded, or displaced from their homes that were destroyed. Almost 20,000 were killed and many more wounded. Cities like Caen and St. Lo were reduced to a pile of rubble. Many other towns were partially runied as the Germans and the Allies traded artillery barges, or when Allied bombers dropped their payloads in advance of the attack. In the process of liberating the Continent, much of it was destroyed. It is significant the the Free French Forces joined the Allied effort with the full knowledge that their country would suffer so much in the process. Following the Normandy Campaign, there would still be months of bitter fighting all through the winter of 1944-45. The Allied Supreme Commander, General Eisenhower, would be challenged not only by the Germans, but also by the infighting among the Allied commanders. However, he successfully led the coalition to complete his mission that he started on June 6th when the Germans finally surrendered unconditionally in May 1945. So, as Prime Minister Churchill aptly stated, although Normandy was not the end, perhaps it was the beginning of the end.

Winston Churchill, Wartime Leader

Winston Churchill, the Prime Minister of Great Britain during World War II, demonstrated great leadership not only for Britain, but for the Allies overall. He was the right man for the moment, and brought great energy and experience to the job. He demonstrated personal courage, inspired his countrymen, and was decisive when crucial decisions were needed. His legacy still remains as one of the great leaders of the 20th century.

Winston Churchill had an interesting and rich experience well before he became the Prime Minister. He was born into an aristocratic English family in the late 19th century and although he was provided the opportunity to attend fine schools, he was not a good student. Ironically, he also had somewhat of a speech impediment. Both of these shortcomings are now mostly forgotten since he later became a prolific writer and a world renowned orator. Eventually, he matriculated at the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst and was commissioned as a cavalry officer in the British Army when he graduated in 1984 near the top of his class. After graduation he saw war up close and personal either as a military observer or as a war correspondent in places like Cuba, India, Sudan, and South Africa. He began is political career as an elected Member of Parliament in 1900, and during the First World War he also served briefly as a battalion commander in the rank of lieutenant colonel in France. He also held a series of important political posts in the government that broadened his experience, especially within the defense establishment. In the years after the armistice that ended WWI, his political fortunes waned while he championed various defense initiatives for tanks, aircraft, and ships as a means to offset the growing power of the German Reich. Although these positions were not popular, they catapulted him into power when Germany invaded Poland in 1939. He replaced Prime Minister Chamberlain who had attempted negotiations with Hitler and then lost favor as German aggression continued. Ironically, Churchill became the Prime Minister on May 10th 1940, the same day that the German Army started the blitzkrieg on the Western Front. Now he was able to draw on his decades of experience to lead his nation in a time of war.

After the Germans had overrun the Low Countries and France, it was the British Empire that virtually stood alone against the German war machine. At a time when it would have been easier to seek accommodation with Hitler, Churchill used his great oratory skills and personal courage to muster the strength of British people to prepare for a long and difficult struggle. Despite the losses of the British Army and much of its equipment at Dunkirk, Churchill rallied his nation. He exhorted his countrymen to fight and prevail in the subsequent air battles known as the Battle of Britain even while English cities and towns were bombed by Germans. The Royal Air Force fought valiently even as it sustained terrible losses of fighter aircraft and pilots while fending off the onslaught. His courageous stance as a leader provided a vision and hope that Britain could prevail over the tyranny and aggression of the German Reich.

After the Americans entered the war following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Prime Minister quickly sought to partner with President Roosevelt to craft a strategy for the way forward. He realistically assessed the situation at the time and correctly evaluated the Allies’ limited capabilities to undertake offensive operations directly against Germany. Although the American military leaders favored an early cross Channel attack, Churchill instead, convinced the President to support a more indirect approach by invading North Africa so that the Allies built up their forces and gained combat experience working together. This was a significant decision that was informed by his deep experience both as a military and political leader. He then tirelessly worked to make sure that the right people were picked for key leadership positions and that they had what they needed to succeed in their mission. Once the Allied forces and leaders had succeeded and gained experience working together, the later then concurred with the Americans to launch the cross Channel attack in 1944.

As with all great leaders, Churchill was a man of vision. He demonstrated personal courage and exercised good judgment on the crucial decisions that were made based on his deep experience from having served in a variety of jobs over the years. His willingness to take risks and use his great oratory skills to communicate and persuade others was instrumental in moving the Allied war effort forward. Without his strong leadership during the war, the history of the second half of the Twentieth Century could have been written quite differently.

For more information follow this link: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Winston_Churchill

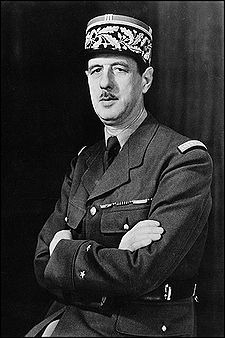

Charles de Gaulle – Leader of the Free French Forces

Charles de Gaulle was the self-anointed leader of the Free French Forces and landed on Juno Beach on June 13, 1944 to assert his authority as leader of the Provisional Government of France following the D-Day invasion.

General de Gaulle was born in 1890 into an aristocratic family that had roots in French Flanders. As a young man, he developed an interest in history and went to college in Paris before deciding on a military career and attending the French military academy, St. Cyr. He graduated from the four year course at St. Cyr and was commissioned as an infantry officer in 1912. During the first World War, he was wounded at the Battle of Verdun in 1916 and taken prisoner by the German Army. After the war, he served in Poland as an instructor to the Polish Army during thier conflict with the Russian army in the early 1920’s. Following his service in Poland, her returned to France and was a staff officer and an instructor at the Ecole Militaire. During this period he became student of armored warfare similar to some of his contemporaries in the German, British and American armies who also were developing theories about maneuver warfare. During these interwar years, he began publishing articles about his theroies and views, which were often criticized by other French officers and senior leaders.

At the beginning of WWII, he was a Colonel in command of a tank brigade, but when the German blitzkrieg attack began, he was quickly promoted to command the French 4th Armored Division and the rank of Brigadier General. Although he lacked air support, he immediately attacked the German army as it was invading France in 1940 and had some limited successes, but could not defeat the superior German force. Eventually, he became the French liason officer to the British, where he sought their help following the surrender of France by Marshal Petain. After fleeing to the safety of England, de Gaulle set about organizing the Free French Forces to oppose the German occupation and fight with the Allies. Despite the support he received from both the British and later the Americans, de Gaulle proved to be a difficult partner for the Allies. He was always suspicious of the Allies’s intentions and they were likewise unsure of de Gaulle. Consequently, they did not include him in their plans for Operation Overlord until the eve of the invasion. Shortly after D-Day, he landed on French soil and quickly moved to take command of all Free French Forces. When Paris was finally liberated, de Gaulle staged a grand entrance and made a famous speech to the French people where upon he was made President of the Provisional Government of the French Republic. He then went about fielding the French First Army which joined the Allies for the invasion of southern France and the eventually defeat the German army. De Gaulle resigned his position after the war, but was later elected President of France with the founding of the 5th Republic in 1958. He held this post until 1969. His tenure is remembered for his strong assertion of French independence and nationalism during the height of the Cold War era of the global struggle between the Western nations and the Soviets. De Gaulle died in 1970 at the age of 80.

As a leader, de Gaulle exemplified the Victory Principles. He certainly had a vision of a free, independent French nation which he championed ardently throughout the period of WWII and thereafter. His values of putting French national interests first often caused him to be a difficult partner to work with from the viewpoint of his allies, but he tenaciously pursued what he thought were the best interests for the French Republic. He demonstrated resilience by overcoming many difficulties in organizing Free French Forces during the war, and asserting his political will over both his political adversaries in France and within the Allied governments to become the leader of the Provisional Government of France. Finally, he always put the interests of his country and team first which was best illustrated by his refusal to accept a pension for his service as president and general, and instead chose to be paid a pension for a colonel, the rank from which he rose at the beginning of the war. Without a doubt he was a controversial leader, but no one can ever say that he put his personal interests ahead of those of his nation or the people. He was a strong leader for France when France needed him.

For more information follow this link: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_DeGaulle