Archive for the ‘Leadership’ tag

Are Your Leaders Ready to Take Charge?

On D-Day, 6 June 1944, General Eisenhower was confident that his soldiers and subordinate leaders were well-trained and ready to accomplish their mission. Leadership is just as important today as is was during World War II. This holds true for any organization whether it is a military unit or a commercial enterprise. With 76 million baby boomers getting ready to retire next year, 2011, many CEOs are being asked: “Are Your Leaders Ready to Take Charge?” Unfortunately in most cases, the answer is that they are not. This is a pending leadership crisis. Learn more about what can be done by reading my latest magazine article: Are Your Leaders Ready to Take Charge?

Pegasus Bridge – Part One – Getting Ready for a High Priority Mission

Within minutes after midnight on June 6th 1944, the first Allied unit landed in Normandy in six British Horsa gliders. Their mission was given the highest priority by General Montgomery, the land component commander and commander of the British 21st Army Group – to assault and seize two bridges, one over the Caen Canal and the other over the Orne River and hold until relieved. Montgomery knew that he had to seize these critical bridges to prevent the Germans from mounting an armored counter-attack. The bulk of the German Panzer units were positioned farther east in the vicinity of Calais, and if they were able to launch such an attack, the Germans would cause havoc with the British 3rd Infantry landing on Sword Beach. A powerful armored thrust could also roll up each of the five Allied beaches one after the other and disrupt all the Allied landings before they could secure a lodgment and bring in reinforcements. Additionally, the British 6th Airborne Division was landing to the east of these bridges and it would be over these bridges that British armored forces would be brought forward from Sword Beach to reinforce the paratroopers and prevent them from being isloated. The high priority mission to capture these bridges in a coup-de-main assault was given to Major John Howard.

Major Howard was a remarkable leader who came up through the ranks. Before the war, he enlisted in the British Army and served for six years attaining the rank of sergeant before he left the service to become a police officer in Oxford. After the war began, he was recalled back to military service. His leadership skill was quickly recognized by his superiors and not only was he promoted to sergeant major, but also selected to receive a commission as an officer. By 1942 he was promoted to the rank of major and commanded D Company, Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry as a part of the elite 6th Airborne Division. Howard was masterful trainer, and relentlessly drove his unit to a high standard of readiness through incessant training exercises. When the Overlord Plan for the invasion was conceived and the requirement arose to seize these key bridges, Howard’s unit was selected because the division commander recognized it as one of his best units. Shortly after the mission was given to Howard, his commander told him that he would be given whatever resources he needed including an additional two platoons of infantry, a platoon of engineers, and even a medical doctor who would accompany the assault. Howard not only continued his tough training regimen, but once he knew his mission and had access to current intelligence about the target, conducted multiple practice runs with a variety of scenarios on mock-ups of the targets.

Eventually, his unit was prepared for almost any imaginable contingency that could arise during this difficult night assault. Howard’s plans called for landing his unit in six gilders within close proximity of the bridges and catch the German defenders off guard. Using surprise and shock action, he planned to quickly overcome any resistance and then set up to defend against a counter-attack. While the assault troops seized the bridges, the engineers would disarm any demolitions that the Germans had set to destroy them rather than have them fall into enemy hands. Since the night landing by gliders was extremely hazardous, Howard prepared his men by making sure that everyone was ready to step up if one or more of the gliders missed the target, or if key people were killed or wounded during the assault phase. As his men went into action it was the intense training that had prepared them for this difficult assignment and gave them high confidence that they could accomplish the mission no matter what happened. They were the first Allied unit to land on French soil and they were ready.

Great Leadership Depends on Great Decisions – Take AIME

All great leaders are defined by the quality of their decisions. Although leaders can delegate, postpone, or otherwise defer decisions, ultimately there are some things that only the leader can decide. As President Harry Truman famously said, “the buck stops here.” He realized that ultimately, he needed to take responsibility and make decisions on the critical issues facing the nation. Likewise, leaders of any organization must also make key decisions and take the responsibility for their outcomes. This philosophy may sound simple, but it doesn’t mean that it is easy. Often leaders must make decisions with scant information. More often than not, there are no clear cut choices among several viable options, and the leader gets conflicting advice about which option to choose. So how can leaders make timely decisions and maximize their chances of making the “right” decision? They rely on a decision making model to help them. Consider the example of the AIME decision making model:

A: Assess the Situation. Whenever they are faced with a decision, leaders assess the situation. This can either be a quick “estimate of the situation” or a more detailed analysis depending on the amount of time available. Regardless, they always assess the situation by considering relevant facts that bear on the problem. Experienced leaders will know intuitively which facts to look at and quickly assess the situation. Experienced emergency room doctors do this all the time. While they seem to easily make quick decisions, in fact, they begin by assessing the patient’s condition by looking at the appropriate vital signs or test results. The reason that they can move quickly to a decision is because of their experience – they have likely seen a similar situation before that they can relate to their present situation. Less experienced leaders (or doctors) will need to get help from trusted colleagues to make their assessment; nevertheless, they must begin the process by looking at the relevant facts.

I: Implement a simple plan. After gathering information to make their decision, the next move is to formulate a simple plan. To create their plan, they will likely consider their viable options. Normally there are no more than five options. If there are more than five, it behooves the leader to quickly eliminate all but the most viable and get to the three best options. Once the options are identified, they compare the advantages and disadvantages of each of the options. If time permits, they sometimes do a deliberate analysis using a decision matrix whereby each option is evaluated against specific “decision criteria.” They might have someone from their staff research the details for each option and present their findings in the form of a comparative analysis which may point to one option that is clearly superior to the others. However once the analysis is completed with whatever detail is permitted due to the time constraints, the leader must choose an option and make their decision.

M: Make it happen. Once the decision is made, then the leader must communicate it to the staff and make it happen. Many leaders assume that once the decision is made and communicated that it is carried out. Don’t assume that once the communication is made, that the decision will automatically get carried out! Even in military organizations where people are accustomed to follow orders, the decisions of senior commanders will not always be carried out as intended. It is up to the senior leader or decision maker to follow up with those who are charged with implementing the decision to see if it is being implemented as intended or if there is an unanticipated problem. This is the time for leaders to “lead from the front.” Get up front and find the problems and fix them, or fire up the people who are supposed to get the job done. Unless you are prepared to rescind or modify the decision, make sure that everyone is on board with getting it implemented. In extreme cases, this might even require firing recalcitrant team members who are obstructing rather than facilitating the decision.

E: Evaluate the decision. This is the last, but most often overlooked step in decision making. Even when leaders follow up to make sure that their decisions are carried out, they often don’t come back later to evaluate the results. Evaluation is really the key to making great decisions. Most leaders understand that they can never make great decisions all the time. Even great leaders will make a poor decision periodically, but the only way to correct that is to evaluate the results. The fact is that even a successful missile launch is off target most of the time. It is up to the guidance system to make mid-course corrections while the missile is in flight so that it gets to the intended target. In the same way, leaders have the ability to achieve their intended results by making periodic reviews of their decisions. Depending on the nature of the decision, the elapsed time before a review may vary widely; however, if everyone knows that there will be a review, they will more diligently carry it out in the first place. Further, they will be looking for signs along the way that will help to make the evaluation more effective. So, make sure to set up a time to evaluate your decisions if you are the leader.

The AIME Decision Model is a simple model to understand, but perhaps not easy to execute in practice; however, using it regularly will instill discipline into the decision making process. This will not guarantee great decisions every time, but it will dramatically increase the probability of making good decisions over the long term. As you get used to applying the model, then it will naturally become easier to use. Make a good decision today and start using the AIME Decision Model.

Leonard Kloeber is an author and consultant. He retired from the US Army Reserves as a Colonel after more than thirty years of service. He also has extensive business experience of over twenty-five years as a hands on leader in a variety of businesses large and small. Most recently he was a human resources executive for a Fortune 100 company. His book – Victory Principles, Leadership Lessons from D-Day – illustrates seven bedrock leadership principles that all successful leaders use. Find out more at: http://www.victoryprinciples.com where you can a download free summary of the Victory Principles. Contact him at info@victoryprinciples.com

Article Source: http://EzineArticles.com/?expert=Leonard_Kloeber

The “Other Guys”

During World War II in Europe, there were multiple personalities who disproportionately received much of the publicity and attention from the press. Students of history will remember the names of Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin because of their high profile positions as heads of state for the major Allied Powers. They would have likely garnered much attention simply due to their positions. Likewise General DeGaulle is remembered as the leader of the Free French, not necessarily for his military prowess, but primarily for his political skills. Most will also recall the names of Eisenhower, Montgomery, Patton, Bradley, and even the German Field Marshal Rommel as the dominate personalities of their respective military commands; however these military leaders, perhaps have received a disproportionate amount of recognition when compared to less well known military commanders. Clearly they made huge contributions, however so did some of the “Other Guys.” On the Allied side, Gen Crear (Canadian), Gen Dempsey (British), Gen Hodges (US), Gen Simpson ( US), Gen Patch (US) and Gen Tassigny (FR) also skillfully led significant army commands in Western Europe and their troops made decisive contributions to the outcome of the war. Likewise on the German side, Field Marshals Von Rundstedt, von Kluge, and Model were key players along with other even lesser known generals in leading their army as it fought the advancing Allies in Western Europe.

So who are these lesser known leaders, and what role did they play in the war? This is the first post in a series that will explore the backgrounds and contributions of these lesser known figures, but who nevertheless played significant roles. Students of both history and leadership will appreciate that it was not just the more well know leaders who were always the most important in determining the outcome in every battle. In war as in peace, sometimes leaders who don’t have the public profile can influence events as much or more than those who receive a disproportionate amount of publicity. Check back here periodically in the future to learn more about these lesser known leaders. The contributions and leadership styles of the “Other Guys” may surprise you.

Here is a intriguing picture of some of them who happened to be Americans:

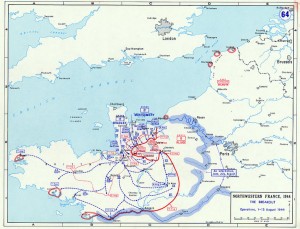

The Normandy Campaign Draws to an End

Sixty-five years ago this month, the Normandy Campaign was coming to an end after almost ninety days of brutal combat between the Allied armies and the German Wehrmacht. It began on June 6th, D-Day when British and American paratroopers jumped into the Cotiten Peninsula to secure key terrain and disrupt the Germans in advance of the assault divisions that landed on five beaches stretching for fifty miles along the coast of Northern France. Their mission was to secure a lodgement, destroy the German forces, and liberate Europe from Nazi tyranny. Although there was bitter fighting right from the start of the invasion, it only grew more intense over the next few months as they fought in the Bocage of the peninsula which was a patchwork of hedgerows. The hedgerows provided a natural defensive position from which the Germans could effectively blunt any Allied advance, and they successfully used machine guns and artillery to great advantage. Despite the Allied advantage in air power and naval gunfire , the Germans put up a stiff resistance. Their army was well trained, had combat experience, and many units, specifically the SS, were fanatical fighters who were dedicated to the Nazi regime.

Over the next few months, Allied commanders launched a series of attacks and utilized their superior air and naval forces to prepare the advance. Tragically, there were many occasions where incidents of friendly fire took place as bombs fell short of their intended targets, and Allied soldiers were killed or wounded even before the operations commenced. Yet they remained fixed on their mission, and demonstrated resilience to continue to pursue the Germans relentlessly. Resilience was crucial to the success for the Allies. It is the simple quality of an organization or individuals to overcome setbacks, and spring back so they can move ahead towards their intended objectives. Time after time, Allied soldiers and their commanders were able to overcome significant losses and rebound in spite of them.

As the weeks past, the Allies continued to bring more men and equipment into the fight while the Germans could not replace their losses. Among the German losses were some senior commanders, include Field Marshal Rommel. He was seriously injured when his staff car was attacked by an Allied fighter plane while he was traveling to visit the units at the front lines of the battle. Visiting the front at the crucial points was his custom and one of the reasons why he was one of the most effective German commanders. As the German losses mounted, their ability to counter attack was diminished. Nevertheless, Hitler demanded more aggressive action from the safety of his headquarters in East Prussia. In frustration, Hitler replaced his Commander-in-Chief, Field Marshal von Rundstedt, with Field Marshall von Kluge. When he arrived in Normandy, Kluge originally thought that the biggest problem for the Germans was a lack of leadership, but as he visited the front lines, he too quickly realized that the German army simply was not able to withstand the onslaught without more replacements and support. On July 20th, an attempt was made on Hitler’s life when a bomb was set off in his bunker in East Prussia, but he sustained only minor injuries. Although his injuries were only minor, he was ruthless in pursuing the perpetrators which included a number of regular army officers. Kluge was concerned about being implicated in the plot, so when Hitler ordered a major counter attack against the Americans from the German left flank, Kluge reluctantly carried out the order even though he knew it was the wrong strategy from purely a military standpoint. This attack at Mortain only played into the Allied plan as it was held in check while the newly activated American Third Army under General Patton broke out of the hedgerow country with his armored and mechanized formations to envelop the flank of the German Army. Within a matter of days, the German attack was completely contained, and the Americans were able to advance almost unopposed into the German rear areas.

Patton drove his troops relentlessly to continue their attack so that the Germans would not have time to recover. This was exactly the right strategy. He exploited success and when necessary even by-passed pockets of resistance to keep up the momentum. By mid-August many of the German units were depleted and beginning to break down under the stress of constant combat. After encircling most of the German Army, the Americans and British attempted to complete the encirclement at Falaise. The Canadians and Poles were attacking from the north towards Falaise while Patton’s Americans and the French 2nd Armored Division were attacking north intending to meet up with them. After reaching Argentan, Patton was ordered to stop his advance to avoid a friendly fire incident with the Canadians and Poles; however, the Canadians and Poles had run into determined resistance from SS Panzer units that were trying to keep the Gap open so that others could escape east across the Seine River to fight another day. In this, they were successful for awhile, but eventually the gap was closed and the Allied air forces relentlessly attacked any Germans on the road moving east. By the end of August, the remaining Germans who were not killed inside the “Falise Pocket” surrendered to the Allies. Knowing that he would be blamed for the defeat, Kluge took his life with a cyinad pill. Meanwhile, the German commander in Paris defied Hitler’s orders to destroy the city and defend it to the last man. He declared it an “open city” and so it was fortunately spared the fate of many of the smaller villages and cites in Normandy that were ruined during the preceding weeks of brutal combat. The Free French Forces under the command of General LeClerc were given the honor to be the first Allied troops to enter Paris.

With the liberation of Paris, the Normandy campaign was officially over, but price in terms of casualties and destruction of property had been great. Not just for the armies, but also for the many French civilians who were killed, wounded, or displaced from their homes that were destroyed. Almost 20,000 were killed and many more wounded. Cities like Caen and St. Lo were reduced to a pile of rubble. Many other towns were partially runied as the Germans and the Allies traded artillery barges, or when Allied bombers dropped their payloads in advance of the attack. In the process of liberating the Continent, much of it was destroyed. It is significant the the Free French Forces joined the Allied effort with the full knowledge that their country would suffer so much in the process. Following the Normandy Campaign, there would still be months of bitter fighting all through the winter of 1944-45. The Allied Supreme Commander, General Eisenhower, would be challenged not only by the Germans, but also by the infighting among the Allied commanders. However, he successfully led the coalition to complete his mission that he started on June 6th when the Germans finally surrendered unconditionally in May 1945. So, as Prime Minister Churchill aptly stated, although Normandy was not the end, perhaps it was the beginning of the end.

VICTORY Principles at-a-glance

VICTORY Principles at-a-glance is a one page overview of the leadership lessons illustrated by the historic events of D-Day that I have written about in my recently published book. As the author, I wanted to provide readers with an easy-to-use reference that would summarize the core principles succinctly so they could keep it as a handy reference. Although my book is based on a World War II narrative, theme of the book is about leadership. My own experience tells me that leadership is an art and not a science. This means that there is no recipe that one can follow that will guarantee that one would become a successful, much less a great leader. However, like all other artists, leaders must work at their craft to perfect their own special style and approach given their own circumstances. Many of the now famous senior leaders during World War II had perfected their leadership skills over the two prior decades between the World Wars. Many of them often toiled in anonymity in jobs that were not very exciting, but which offered them the opportunity to practice their craft as leaders. It was because of their experience that they were ready to assume the positions of much greater responsibility when the time came. So if you aspire to be a successful leader, take advantage of any opportunity you have in front of you to start learning your craft.

Despite the wide range of styles and approaches of successful leaders, I truely believe that there are certain bedrock leadership principles that all leaders incorporate into their approach. Leaders who don’t follow these principles will likely never succeed to their full capability, even if they achieve some level of success. After spending a significant part of my own career in leadership positions and observing other leaders around me, I have identified these seven principles that I believe all leaders rely upon. You can find these VICTORY Principles at-a-glance in a PDF document that you can download by searching the tool bar to the right under bonus documents or you can click on this link:

VICTORY Principles at-a-glance

Learn from History: Innovation Leads to Success

War is one of the most tragic of all human endeavors when measured in loss of life and property, suffering of all the participants, and the cost of rebuilding after the final shot has been fired. In spite of the horrific consequences of war, it illustrates that even under the harshest of circumstances, innovation and learning are critical to survival and also essential ingredients to success. Students of history will understand that successful military operations have been the result of “learning on the fly.” Successful armies learn how to defeat the enemy by adapting to their tactics, by innovating new tactical solutions of their own, and by finding new ways to use the resources available. These same concepts of learning apply to success in business by adapting your competitor’s tactics and leveraging your own resources in the marketplace. While the analogy of war and business is not perfect, it does offer some valuable insights. Let’s look at the Normandy campaign in World War II as an example.

After the Allied armies had established a beachhead on the Normandy coast of France following the D-Day invasion on June 6th 1944, the fighting became protracted and intense in the Norman hedgerows. Many of the objectives that were expected to be achieved in the first few days were not actually realized until a month or more into the campaign as the fighting bogged down in the “Bocage” country. This was where farmers had raised their cattle and grown crops since before Norman the Conqueror had left the same area to sail across the English Channel almost 1000 years before. Over the centuries they had built natural fences from mounds of dirt where they planted shrubs and trees to form barriers of dense vegetation to separate their fields. These are known as hedgerows. Usually the hedgerows surrounded a field and only had a small opening from which you could enter the enclosed area. Hedgerows provided the Germans with natural defensive positions from which to defend against the advancing Allied armies. By strategically emplacing machine guns that targeted the entrances to these fields and also using pre-arranged artillery and mortar fire, they could easily slow down an Allied advance and inflict many casualties. Even tanks were vulnerable to attack when they penetrated the hedgerows through the natural openings and were hit by anti-tank weapons and artillery.

Then one day, Sergeant Curtis G. Culin of the American 102nd Cavalry, 2nd Armored Division decided that if he could weld some steel prongs on his tank, then he could literally plow through a hedgerow at an unexpected place quickly and avoid the pre-sited German fire. It worked! General Omar Bradley, then in command of the American army, ordered this adaptation be made to tanks in other units too. Ironically they were able to use the same steel girders that the Germans had used for beach obstacles as a source for the metal needed to modify the tanks. Thereafter, the Allied armies were able to more easily attack into the hedgerows with fewer casualties. This innovation and learning under fire saved American lives and contributed to the eventual defeat of the German army in Normandy. It is but one good example of how “learning on the fly” can lead to success, even where the concept is quiet simple and maybe even obvious once it is implemented.

This same concept of learning and innovation can also be applied to business. One of the industries that has thrived on innovation and learning to improve products and services is the fast food industry. Competitors in this industry constantly look for ways to do things easier, faster, and more reliably. You can find examples at McDonalds where they have used innovations over the years to cook their French Fries and hamburgers uniformly or make milk shakes quickly, or at Taco Bell where they have perfected the art of making a taco or enchilada. They have done this by designing kitchen equipment that is almost foolproof and produces similar results each time, even where their workers may have limited experience. Often these innovations come from their franchisees who have learned lessons the hard way and not from the corporate headquarters. So it is important for leaders to be alert and listening to those on the front lines, just as General Bradley listened to Sergeant Culin sixty five years ago.

Make learning and innovation a part of your organization. Experiment. Take small risks. Try new approaches. Small successes and innovations when taken together can have a huge impact on the bottom line and your overall results. If you are a leader, encourage this kind of behavior and make it a part of the organizational culture. Be careful not to stifle this activity by punishing failure. Often the experiments may not work, but when they do, the can have a big payoff. If you punish people who try and fail, word will get around quickly. Others will choose to play it safe and not look for ways to improve. So if you want to encourage innovation you need to positively encourage your people even when they fall short. Obviously, you should also celebrate success when someone tries and succeeds. Public recognition will also get the message across that you want to look for ways to improve. So start by looking for the small wins, and then build from there. Make innovation and learning a part of your success.

Winston Churchill, Wartime Leader

Winston Churchill, the Prime Minister of Great Britain during World War II, demonstrated great leadership not only for Britain, but for the Allies overall. He was the right man for the moment, and brought great energy and experience to the job. He demonstrated personal courage, inspired his countrymen, and was decisive when crucial decisions were needed. His legacy still remains as one of the great leaders of the 20th century.

Winston Churchill had an interesting and rich experience well before he became the Prime Minister. He was born into an aristocratic English family in the late 19th century and although he was provided the opportunity to attend fine schools, he was not a good student. Ironically, he also had somewhat of a speech impediment. Both of these shortcomings are now mostly forgotten since he later became a prolific writer and a world renowned orator. Eventually, he matriculated at the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst and was commissioned as a cavalry officer in the British Army when he graduated in 1984 near the top of his class. After graduation he saw war up close and personal either as a military observer or as a war correspondent in places like Cuba, India, Sudan, and South Africa. He began is political career as an elected Member of Parliament in 1900, and during the First World War he also served briefly as a battalion commander in the rank of lieutenant colonel in France. He also held a series of important political posts in the government that broadened his experience, especially within the defense establishment. In the years after the armistice that ended WWI, his political fortunes waned while he championed various defense initiatives for tanks, aircraft, and ships as a means to offset the growing power of the German Reich. Although these positions were not popular, they catapulted him into power when Germany invaded Poland in 1939. He replaced Prime Minister Chamberlain who had attempted negotiations with Hitler and then lost favor as German aggression continued. Ironically, Churchill became the Prime Minister on May 10th 1940, the same day that the German Army started the blitzkrieg on the Western Front. Now he was able to draw on his decades of experience to lead his nation in a time of war.

After the Germans had overrun the Low Countries and France, it was the British Empire that virtually stood alone against the German war machine. At a time when it would have been easier to seek accommodation with Hitler, Churchill used his great oratory skills and personal courage to muster the strength of British people to prepare for a long and difficult struggle. Despite the losses of the British Army and much of its equipment at Dunkirk, Churchill rallied his nation. He exhorted his countrymen to fight and prevail in the subsequent air battles known as the Battle of Britain even while English cities and towns were bombed by Germans. The Royal Air Force fought valiently even as it sustained terrible losses of fighter aircraft and pilots while fending off the onslaught. His courageous stance as a leader provided a vision and hope that Britain could prevail over the tyranny and aggression of the German Reich.

After the Americans entered the war following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Prime Minister quickly sought to partner with President Roosevelt to craft a strategy for the way forward. He realistically assessed the situation at the time and correctly evaluated the Allies’ limited capabilities to undertake offensive operations directly against Germany. Although the American military leaders favored an early cross Channel attack, Churchill instead, convinced the President to support a more indirect approach by invading North Africa so that the Allies built up their forces and gained combat experience working together. This was a significant decision that was informed by his deep experience both as a military and political leader. He then tirelessly worked to make sure that the right people were picked for key leadership positions and that they had what they needed to succeed in their mission. Once the Allied forces and leaders had succeeded and gained experience working together, the later then concurred with the Americans to launch the cross Channel attack in 1944.

As with all great leaders, Churchill was a man of vision. He demonstrated personal courage and exercised good judgment on the crucial decisions that were made based on his deep experience from having served in a variety of jobs over the years. His willingness to take risks and use his great oratory skills to communicate and persuade others was instrumental in moving the Allied war effort forward. Without his strong leadership during the war, the history of the second half of the Twentieth Century could have been written quite differently.

For more information follow this link: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Winston_Churchill

Maximize Performance Using After-Action-Reviews

In these tough economic times, maximum performance is not only necessary for a company’s growth, but in many cases it is a critical component of a survival strategy. Optimum performance is required both at an individual and organizational level. If you can improve performance and efficiency in your operations, you will beat your competition and win over loyal customers for the future. Similar to the Japanese strategy for constant improvement, Kaizan, you can borrow a technique that is extensively used by the military to improve the performance of their units in training and combat. This simple, but effective technique is known as an After Action Review, or more simply, an AAR.

Over the years, military organizations have effectively used AAR’s as a team learning technique to improve their performance in both training and combat operations. This simple concept can be adapted easily to commercial or non-profit enterprises with similar positive impact. An AAR in its basic format is an organized review of an operation just completed. It is a “discovery learning” exercise that seeks to understand how similar operations can be improved for the future. In order to conduct an effective AAR, the stage should be set by the leader to establish a non-threatening environment where all participants are free to share their perspective without fear of reprisals. In the military, this means that rank takes a back seat to seeking the truth about what went right, what went wrong, and what can be improved. In this way, a robust and honest discussion will focus on what can be improved for the future. Here are some logical steps to conduct an AAR for your team:

1. Set the stage and ground rules: It is incumbent upon the leader of the organization to set the stage. This means that he or she should start by explaining the purpose and outcomes for the AAR session. The purpose of the AAR is to have an honest and robust discussion of a completed operation or project so that the team can discover “lessons learned” for the future. The primary outcomes are in the form of operational changes that lead to improved performance. At the session, everyone should feel free to speak their minds about what they observed or experienced during the operation. Additionally the leader should encourage participation by everyone on the team, even those who are normally reserved. Many times, these people will offer some of the best insights. The leader should also establish ground rules for respectful, but honest discussion. This will require courage on the part of the leader, especially when the leader’s own actions may be critiqued as part of the discussion. However, good leaders will welcome honest feedback on how they can personally improve their performance in support of the team, and if handled correctly, will enhance the leader’s trust with the rest of the team. Similarly, others should embrace feedback for their own actions as part of overall team improvement, and this will happen if the leaders set the right tone. The trick is to focus on effectiveness of behaviors and actions, but not on individual personalities.

2. Discuss the concept of the operation first: Begin the AAR by establishing the concept of the operation: What was the mission? What were the intended outcomes? What was the leader’s guidance to the team? What were the team members’ understanding of their roles? What were the standards if any for performance? What was the plan? How was it communicated? Note that the key to a successful AAR is to have a planned list of questions that will guide the conversation and enhance the group’s detailed understanding of the operation. The challenge for the discussion leader in this part of the discussion is to keep the focus on what was planned rather than jump into what actually happened which will come next.

3. Discuss what actually happened: Go through each step of the operation and focus on what actually happened. Typically this is done chronologically, starting with the first steps and progressively discussing each subsequent step until the operation was concluded; however, sometimes it may make sense to conduct a functional discussion of the operation meaning that things may be discussed by function rather than chronologically. This could mean that the actions of a support group or the leader’s actions are addressed as a separate discussion if this will help to focus on these specialty areas. However, in leading the discussion using this format, be sure to not loose perspective on how all the aspects of an operation fit together as a whole system.

4. Discuss what went well: This part of the discussion will focus on those things that went “right” and should be sustained in future operations. It is very important to focus on those actions that positively contributed to success, since you will want to deliberately make sure that these actions are continued in the future. This will include those things that were planned and executed well, and also those things that were unplanned, but nevertheless contributed to a positive result. Discussing the things that went right first will not only provide support for the team through positive recognition, but will offset the subsequent discussion of those things that didn’t work. This will result in a more balanced discussion overall.

5. Discuss those things that didn’t go well: This is where some of the best lessons are learned for the future, but it requires people to be bold enough to honestly report what did not go well. There may be things that were not planned for ahead of time, inadequate resources, poor instructions, lack of training, inappropriate leadership actions, or failure of individual team members to do their specific jobs. Sometimes these discussions will be difficult because people will tend to naturally defend their performance; however, if the discussion can be based on facts rather than opinions some of these personal challenges can be avoided. It will be up to the discussion leader to moderate the tone of the discussion and avoid any personal attacks which would be counterproductive to a learning environment.

6. Discover “lessons learned” for the future: Conclude the discussion with a discovery learning session about what was learned and how things can be improved for the future. Often this will be the most engaging part of the AAR. There may be a wide range of issues, but more often than not, there will be just a few critical issues that will have the most impact on the outcomes for the team. Try to avoid an extremely detailed discussion of those issues that will have a minimal impact, and focus instead on the most critical issues. Most teams will likely only be able to incorporate so much change at any one time so you will only want to address the most important issues first. The leader will want to make sure that the operational changes made in the future will be those which have the biggest pay-off for the team.

The format of your AAR can be adapted from these basic steps, but the general thrust of the AAR is to discover the “lessons learned.” Thus, if it makes sense for your team to capture these lessons as you go through the discussion, then the last step can simply be used to summarize the lessons that you have captured in the earlier steps. Regardless of your sequence, you should end the session with a commitment to make some common sense changes for improvement. Failure to make any changes will simply be frustrating for all participants and will make future AAR sessions more difficult. Your team will expect to see some positive results from the AAR, so this is your opportunity to drive positive change for your organization. If your team gets into the habit of regularly holding AAR sessions, they will become easier, quicker, and more effective. The best way to get started is to just hold an AAR at the conclusion of your next project or operation, even if the AAR isn’t done perfectly. The sooner your team has a chance to discover how they can improve, then the sooner you can actually see positive results. Use this article as your checklist for your AAR and get started now!

Note this post has been submitted for publication at ezinearticles.com

Seven Bedrock Leadership Principles Used by all Successful Leaders

There are seven bedrock leadership principles that all leaders use. These are principles and not prescriptions. Hence, leaders must tailor the application of the principles to their unique organization and in their own way. Despite their unique application, these principles are the underpinnings of all successful leadership endeavors. Here are the common treads of successful leadership:

1. Vision: All great leaders have an inspiring vision of the future which provides direction and hope for a better day. They are effective at communicating and building support for their vision to get everyone in their organization on board. Effective leaders usually enlist the support of key followers to help craft their vision. This builds trust and confidence, and also leverages the unique talents and perspectives of others within the organization.

2. Innovation and Learning: Leaders are always looking for better ways to accomplish their objectives and they encourage people to experiment with new approaches and learn from them. Sometimes the innovations don’t work out as planned, but good leaders will encourage their people to quickly learn from the experience and move on to try another approach. When they find an approach that works, they quickly move to exploit their success. They avoid placing blame for failure and share the glory for success with the team.

3. Capabilities – People and Resources: All great leaders are looking for people with the right skills to have on their team; they also know that even the best people must have the right resources to be successful. Leaders take it upon themselves to obtain the right people and the right resources for their team. They are the lead talent scouts and take on the responsibility to find whatever is needed to get the job done.

4. Timely Decisions: Leaders make timely decisions so their organization can move forward. Furthermore they have a disciplined approach to decision making that often involves the use of a decision making model. They know that they will not always make the right decision, but by having a disciplined approach to decision making that they can increase their odds of success. They also periodically review their decisions and make appropriate course corrections to move towards their goals.

5. Operating Principles and Values: Great leaders know that the best way to influence their organization is through the use of operating principles and values. Operating Principles and Values establish a framework for behavior within the organization and allow people to act in concert with the positive cultural norms. This is how leaders empower others in the organization to take action when needed without resorting to command and control style leadership by giving orders from the top.

6. Resilience: Leaders know that the path to success is not a straight line. There are always obstacles along the way that must be overcome. The skill of overcoming obstacles and pushing through resistance is called resilience. Leaders themselves must be resilient to overcome setbacks, and they must instill this quality in their people and the organization as a whole. The best way to do this is by example. In times of crisis, people will look to the leader to see how they behave. If the leader maintains their cool under fire, and pushes ahead, others will follow. This is the principle of resilience in action.

7. Your Team: Leaders put their team first. They make sure that every team member knows what is expected of them; that they are trained to do their job; and that they are taken care of as individuals. Leaders who take good care of their people know that the people will take care of them when the chips are down because they have earned their trust. Great leaders “lead from the front.” They go where the action is to be with their team so that they have a deep understanding of what the real issues are that their people are dealing with on a daily basis. This creates trust, provides critical information for the leader upon which they can base their decisions, and demonstrates genuine concern for the people and the organization.

Applying these principles will not guarantee your success; however, if you fail to use them, you will not be an effective leader. All great leaders use these principles, but also use their own leadership style to implement them. If you observe great leaders in action, you will find them using these principles to lead their organizations to success.

This article wass recently published in www.ezinearticles.com and can be viewed at the following link:

http://ezinearticles.com/?Seven-Bedrock-Leadership-Principles-That-All-Great-Leaders-Use&id=2400285