Archive for the ‘Eisenhower’ tag

Operation Fortitude: The Art of Deception

The famous Chinese military strategist, Sun Tzu is credited with saying that “All war is deception,” meaning that a skillful general will deceive his opponent so that he can increase his odds of success. During World War II, Operation Fortitude in support of the Allied invasion of France was one of the best examples of the use of deception to support military operations at any time in history. The intent of the Fortitude Plan was to convince the Germans that the Allies would most likely strike at the Pas de Calais on the expected cross-Channel attack so that the German army would concentrate a significant portion of their forces away from the Normandy area. At the same time, another part of the Fortitude plan threatened a strike in Norway with the intent to also cause them to have to defend that area as well. When the landings occurred in Normandy on June 6th the German High Command considered this to be a diversion. They held a significant portion of their best armored units in reserve believing that the real attack would come later; but in fact, Normandy was the main assault. As the Supreme Commander, General Eisenhower understood exactly what Sun Tzu had in mind.

The deception was partly predicated on the German belief that the Pas de Calais was the most likely place to mount a cross-Channel attack because it was the shortest route from England. This would shorten the Allied logistical lines which would maximize air support from aircraft based in southern England, as well as maximize the sealift capability by minimizing the time required for a ship to deliver its cargo and return for another trip. Allied intelligence realized this German pre-disposition, so the Fortitude plan was created to support their thinking. A fictitious army complete with dummy tanks, trucks, and tents was set up in southern England under the command of American General George S. Patton. Patton was considered perhaps the best Allied field commander, and so this added to the deception; however, Patton was in actuality being temporally “benched” by Eisenhower for his misconduct in Sicily where he slapped some soldiers in field hospitals who were suffering from “battle fatigue.” While Patton’s stated intentions were to shame the soldiers into returning to their units and rejoin the fight, the press reported the incident which outraged politicians on the home front. So to defuse the situation while still keeping Patton available for future operations, Eisenhower assigned him to command the phantom First US Army Group. German agents soon reported his presence which helped to support the deception story.

Additionally, the Allies conducted routine, but false, radio traffic which they knew would be intercepted by German intelligence. This also created the impression that the First US Army Group was active. They also periodically moved some of the mocked up tanks and trucks, and created tracks in the fields to make it look as if they were moved so that if the Germans flew aerial reconnaissance, they would believe that there was in fact a real army on the ground. However, because the German Luftwaffe was under constant attack by the Allied air forces, they likely did not overfly the area. Nevertheless, the British intelligence had also turned some of the German agents into double agents, so their stories of Allied army activities which they reported back to their German handlers seemed all the more real and part of a coherent story.

The Fortitude pan was successful in achieving is intended result s. The old military maxim held true: he who defends everywhere, defends nowhere. Although the landings in Normandy were strongly contested by the German defenders from fortified positions, the Allies succeeded in part because the bulk of the German armored units were not committed to a strong counter attack sooner. By the time the Germans realized that this was the main assault, the Allies had already obtained a strong foothold on the Continent, and it was too late to dislodge them. Sun Tzu could have predicted the result.

December 1944 -Winter in the Bulge

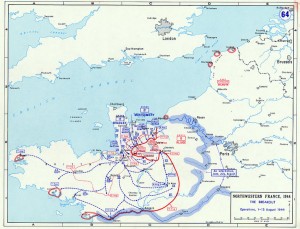

Near the end of the Normandy Campaign on August 15, 1944, the Allies launched another assault through southern France, code named Operation Dragoon. Originally this was planned to be a concurrent operation with the Normandy landings so as to be mutually supporting; however, due to a shortage of available shipping, General Eisenhower reluctantly postponed Operation Dragoon until August. Although Dragoon was slightly smaller in size and scope than Operation Overlord in Normandy, the Allies still landed a formidable force of almost 100,000 soldiers and over 10,000 vehicles on the first day alone. After overcoming initial resistance, the Allies continued to bring in more men and supplies, and opened the major port of Marseilles. These port facilities were needed not only to support the additional troops for Dragoon, but to supply the entire Allied force on the Western Front. Both of the Allied armies from Overlord and Dragoon eventually linked up in mid-September near Dijion, France, as they continued to press their retreating German adversaries across the entire length of Western Europe.

Also in September, General Eisenhower authorized British General Montgomery to conduct Operation Market Garden which was intended to be a lighting strike through Holland and into Germany across the Rhine River. His plan was to use three airborne divisions to seize critical bridges in Holland which would be used by an armored force thrusting from the Belgium border across Holland and into Germany by crossing the Lower Rhine River at Arnhem. The two pronged Market-Garden plan was given priority for supplies and logistics among other Allied operations. This infuriated other American commanders, particularly General Bradley and General Patton who had to restrain his Third Army and conduct only limited attacks further south in France while Market-Garden was in progress.

The Market-Garden battle did not unfold as Montgomery had planned: Most of the bridges were seized after heroic action by the paratroopers, except for the last one at Arnhem over the Rhine as the armored columns were delayed along the way. Consequently, the Allies got mired in Holland instead of making it into Germany. The British paratroopers could not hold onto the Arnhem bridge until relieved and sustained many casualties until they were ordered to withdraw those who could still make it back to rejoin the Allied line. From then on the phrase “a bridge too far” was born to explain what happened, and this phrase is now commonly used to describe stretch goals which are unlikely to be achieved in whatever the endeavor.

Yet despite the disappointment in Operation Market-Garden, the German army had been taking horrendous losses on both the Western and Eastern Fronts as well as in Italy. Thus, many observers and soldiers alike were envisioning a quick Allied victory and some even predicted that hostilities would end by December, but this also was not to be so. Hitler had been planning his own major thrust through the Ardennes Forest to knock the momentum out of the Allied advance and split their force in two by launching a blitzkrieg strike from lower Belgium into the Allied line towards the North Sea port of Antwerp on the coast. He hoped that if he could succeed, he might be able to get the Western Allies to agree to a separate peace accord so that he could focus his attention on the Red Army in the east. So, in October and November, the Germans began massing their panzer forces for a December attack through the Ardennes where the Allies had considered it to be unlikely that the Germans would be able to conduct offensive operations. The Germans were counting on the element of surprise in addition to a swift advance, and if everything went their way, the winter weather conditions would limit the Allies from using their vastly superior air forces.

Initially the Germans got lucky, and their attack, which began with a massive artillery barrage on December 16th, was soon followed up with a blitz by their panzer units. They pushed through the American lines where Eisenhower has posted a mixed group of new units, and combat hardened units that were recuperating on what was considered the “quiet front.” The resulting German advance created “bulge” in the Allied line and hence the largest battle on the Western Front ,and the largest for American forces in any theater of WWII, would be known thereafter as the “Battle of the Bulge.” While the combat experienced units put up a valiant defense in the face of overwhelming German forces, the inexperienced units mostly fell back in disarray and many soldiers were taken as POWs in front of the advancing Germans.

Eisenhower quickly moved into the breach some of his experienced units that were being held in reserve including the paratroopers from the American 82nd and 101st Airborne divisions, but they were not equipped for winter warfare and were short on ammunition and supplies. The 101st was sent to the town of Bastogne where there was a junction of the main roads that ran through the area. If this town could be held, then it would likely stall the German advance and buy time for additional Allied forces to be brought into the fight.

While the paratroopers who were supported by some available armor units from the American 10th Armored Division dug in around Bastogne, Eisenhower called a conference with his major commanders to deal with the situation. As the Germans had hoped, the weather kept the Allied aircraft on the ground, and they were able to maneuver more freely such that they surrounded the pocket around Bastogne by December 21st. At the Allied commander’s conference, General Patton announced that he could redirect elements of his Third Army that were positioned to the south of the pocket to begin an attack north within 48 hours much to the surprise of the other senior commanders. The Allied commanders then set forth to counter-attack the Germans from the south with Patton’s Third Army and also from north with a combined American and British effort forming a pincer to cut off the German advance and relieve Bastogne. They planned to turn the unexpected crisis into an opportunity to defeat the Germans who were now mired in the bulge without supplies and reinforcements of their own.

As promised, Patton began his advance north towards Bastogne, but the northern force did not begin simultaneously because General Montgomery, who was generally a more cautious commander, wanted more time to prepare his units. This was also controversial since Eisenhower had placed the American First and Ninth Armies, a part of Bradley’s command, under Montgomery because the bulge had cut them off from Bradley’s HQ. It was primarily the Americans who would also attack from the north, and not the British. Meanwhile the Germans had sent an ultimatum message requesting the US commander in Bastogne to surrender his forces or be destroyed. Despite the dreadful conditions and shortages of ammunition and food, General Anthony McAuliffe, acting commander of the 101st Airborne answered with a one word reply – “nuts!” As the weather conditions improved on December 23rd the Allied air forces were able to attack the German panzer formations and provide limited supplies by air to the embattled forces in Bastogne. The improved weather conditions also allowed the Third Army to continued their attack, and they eventually reached Bastogne by December 26th bringing additional supplies and evacuating the wounded.

A frustrated Eisenhower urged Montgomery to finally commence his attack from the north on January 1st 1945, however, Montgomery did not get going until January 3rd due to another snowstorm. Nevertheless, the British and American forces in the north had played an important part in the battle by thwarting the German advance towards their primary objective, Antwerp, and now that they began their counter-attack, the Germans were forced to pull back to their original lines – but leaving most of their armor and heavy equipment behind. Just as had happened in Normandy, the Allies had failed to fully shut the back door on the retreating German army, but they had substantially depleted their ability to conduct any more offensive operations having suffered estimated 80 – 100,000 casualties and losses of critical equipment. Although the Americans had also suffered a similar loss, it was the Germans who were now totally defensive whereas the Americans could continue to replace losses in men and equipment. Following the battle, Winston Churchill said of the Americans: “This is undoubtedly the greatest American battle of the war and will, I believe, be regarded as an ever-famous American victory”.

The Normandy Campaign Draws to an End

Sixty-five years ago this month, the Normandy Campaign was coming to an end after almost ninety days of brutal combat between the Allied armies and the German Wehrmacht. It began on June 6th, D-Day when British and American paratroopers jumped into the Cotiten Peninsula to secure key terrain and disrupt the Germans in advance of the assault divisions that landed on five beaches stretching for fifty miles along the coast of Northern France. Their mission was to secure a lodgement, destroy the German forces, and liberate Europe from Nazi tyranny. Although there was bitter fighting right from the start of the invasion, it only grew more intense over the next few months as they fought in the Bocage of the peninsula which was a patchwork of hedgerows. The hedgerows provided a natural defensive position from which the Germans could effectively blunt any Allied advance, and they successfully used machine guns and artillery to great advantage. Despite the Allied advantage in air power and naval gunfire , the Germans put up a stiff resistance. Their army was well trained, had combat experience, and many units, specifically the SS, were fanatical fighters who were dedicated to the Nazi regime.

Over the next few months, Allied commanders launched a series of attacks and utilized their superior air and naval forces to prepare the advance. Tragically, there were many occasions where incidents of friendly fire took place as bombs fell short of their intended targets, and Allied soldiers were killed or wounded even before the operations commenced. Yet they remained fixed on their mission, and demonstrated resilience to continue to pursue the Germans relentlessly. Resilience was crucial to the success for the Allies. It is the simple quality of an organization or individuals to overcome setbacks, and spring back so they can move ahead towards their intended objectives. Time after time, Allied soldiers and their commanders were able to overcome significant losses and rebound in spite of them.

As the weeks past, the Allies continued to bring more men and equipment into the fight while the Germans could not replace their losses. Among the German losses were some senior commanders, include Field Marshal Rommel. He was seriously injured when his staff car was attacked by an Allied fighter plane while he was traveling to visit the units at the front lines of the battle. Visiting the front at the crucial points was his custom and one of the reasons why he was one of the most effective German commanders. As the German losses mounted, their ability to counter attack was diminished. Nevertheless, Hitler demanded more aggressive action from the safety of his headquarters in East Prussia. In frustration, Hitler replaced his Commander-in-Chief, Field Marshal von Rundstedt, with Field Marshall von Kluge. When he arrived in Normandy, Kluge originally thought that the biggest problem for the Germans was a lack of leadership, but as he visited the front lines, he too quickly realized that the German army simply was not able to withstand the onslaught without more replacements and support. On July 20th, an attempt was made on Hitler’s life when a bomb was set off in his bunker in East Prussia, but he sustained only minor injuries. Although his injuries were only minor, he was ruthless in pursuing the perpetrators which included a number of regular army officers. Kluge was concerned about being implicated in the plot, so when Hitler ordered a major counter attack against the Americans from the German left flank, Kluge reluctantly carried out the order even though he knew it was the wrong strategy from purely a military standpoint. This attack at Mortain only played into the Allied plan as it was held in check while the newly activated American Third Army under General Patton broke out of the hedgerow country with his armored and mechanized formations to envelop the flank of the German Army. Within a matter of days, the German attack was completely contained, and the Americans were able to advance almost unopposed into the German rear areas.

Patton drove his troops relentlessly to continue their attack so that the Germans would not have time to recover. This was exactly the right strategy. He exploited success and when necessary even by-passed pockets of resistance to keep up the momentum. By mid-August many of the German units were depleted and beginning to break down under the stress of constant combat. After encircling most of the German Army, the Americans and British attempted to complete the encirclement at Falaise. The Canadians and Poles were attacking from the north towards Falaise while Patton’s Americans and the French 2nd Armored Division were attacking north intending to meet up with them. After reaching Argentan, Patton was ordered to stop his advance to avoid a friendly fire incident with the Canadians and Poles; however, the Canadians and Poles had run into determined resistance from SS Panzer units that were trying to keep the Gap open so that others could escape east across the Seine River to fight another day. In this, they were successful for awhile, but eventually the gap was closed and the Allied air forces relentlessly attacked any Germans on the road moving east. By the end of August, the remaining Germans who were not killed inside the “Falise Pocket” surrendered to the Allies. Knowing that he would be blamed for the defeat, Kluge took his life with a cyinad pill. Meanwhile, the German commander in Paris defied Hitler’s orders to destroy the city and defend it to the last man. He declared it an “open city” and so it was fortunately spared the fate of many of the smaller villages and cites in Normandy that were ruined during the preceding weeks of brutal combat. The Free French Forces under the command of General LeClerc were given the honor to be the first Allied troops to enter Paris.

With the liberation of Paris, the Normandy campaign was officially over, but price in terms of casualties and destruction of property had been great. Not just for the armies, but also for the many French civilians who were killed, wounded, or displaced from their homes that were destroyed. Almost 20,000 were killed and many more wounded. Cities like Caen and St. Lo were reduced to a pile of rubble. Many other towns were partially runied as the Germans and the Allies traded artillery barges, or when Allied bombers dropped their payloads in advance of the attack. In the process of liberating the Continent, much of it was destroyed. It is significant the the Free French Forces joined the Allied effort with the full knowledge that their country would suffer so much in the process. Following the Normandy Campaign, there would still be months of bitter fighting all through the winter of 1944-45. The Allied Supreme Commander, General Eisenhower, would be challenged not only by the Germans, but also by the infighting among the Allied commanders. However, he successfully led the coalition to complete his mission that he started on June 6th when the Germans finally surrendered unconditionally in May 1945. So, as Prime Minister Churchill aptly stated, although Normandy was not the end, perhaps it was the beginning of the end.

Learn from History: Leadership requires a vision

Sixty-Five years ago, Allied armies under the command of General Dwight D. Eisenhower stormed the beaches at Normandy to liberate Europe and end World War II. This was and still remains one of the most complex military operations ever undertaken. It was planned and executed without the help of modern communications and computers that we now take for granted. So what can we learn from these historical events of over a half century ago that could help us today? Leadership.

The successful Allied invasion was the result of superior leadership starting with General Eisenhower, the Supreme Commander, and continued all the way down to the sergeants and junior officers that led the troops into battle. While the Germans also had some good individual leaders like Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, as a group, the did not share the same vision on how they would defend the beaches. Thus, what started as a foothold on the continent by the Allies grew into a major assault that could not be contained. The leadership provided by General Eisenhower and his subordinates became a major factor as the Allies fought together as a team. The Allies were able to eventually land enough troops and supplies while the Germans could not replace their losses. After some very difficult fighting, the American Third Army under the leadership of General Patton broke through the German lines. Once the breakout occurred the Germans were about to be surrounded. Those that could escape to fight another day retreated while the vast majority were either casualties or became prisoners of war.

The same principles of leadership used by the Allied commanders are universal leadership principles that can applied even today. Given the complex challenges facing the country, it will be excellent leadership that carries us forward to a better day, just as it did sixty-five years ago.

Today more than ever, strong leadership is required to solve the major challenges facing our country and the world. Business leaders need to provide strong leadership to their organizations in a weak economy. Others need to solve major problems on energy, health care, and global warming. Although these historic leadership lessons were forged in the heat of a desperate battle on D-Day, the common element that still remains is human nature. Leadership is the skill that gets things done, solves problems and moves us to a better day. We need effective leaders at all levels and in a cross section of business, non-profit, as well as government enterprises. Thus, the same principles that were used by Allied leaders to achieve victory then, can be used today to lead us forward.

A good example of a leadership principle in action is the concept of “vision.” General Eisenhower provided a vision of his plan for a successful invasion. The plan was known as Operation Overlord. All leaders must have a compelling vision of the future. This defines where they want to go and provides their followers an element of hope of success for the future. Although this is a simple, and perhaps obvious component of good leadership, it is easier said than done. Crafting a compelling vision requires a leader to have a deep understanding of his or her operating environment, the capabilities and limitations of their organization, and a clear understanding of their strategy for moving ahead. Good leaders involve their people to help them develop their vision. This creates organizational buy-in and builds support within the organization. Thus, vision is a fundamental component of good leadership. If you plan to be a successful leader, learn from history and make sure that you have a compelling vision to inspire your followers.

The Supreme Commander: General Dwight D. Eisehhower

Gen. Eisenhower visits 101st Airborne just before D-Day on June 5th 1944 at their airfield in England

In December 1943, President Roosevelt announced that General Dwight D. Eisenhower would be designated as the Supreme Allied Commander to lead the combined Allied forces for the invasion of Europe on D-Day, June 6th 1944. Eisenhower graduated from the US Military Academy at West Point with the Class of 1915. He began his military career in the infantry and served stateside during World War I, much to his chagrin. He later was assigned to served in the new tank corps and after the war was over, developed a close friendship with a fellow tank corps officer, George S. Patton. Like many officers in the post World War I army, his career progression stagnated; however he made some close associations with mentors like General Fox Conner and later General Douglas MacArthur whom he accompanied to the Phillipines when MacArthur retired from the US Army to train the Philippine Army. Eisenhower also distinguished himself by graduating first in his class at the army Command and General Staff College at Ft. Leavenworth, Kansas.

When World War II began in Europe, Eisenhower was reassigned back to the US and after a series of assignments was brought to Washington DC to serve under the Army Chief of Staff, General George C. Marshall, as the head of the War Plans Divsion. He was quickly promoted to Brigadier General in this assignment, and although he was a relatively junior general officer, he demonstrated his ability not only for planning, but more importantly for dealing with people who had strong personalities and were often senior in rank. These were leadership qualities that were noticed by General Marshall and at his urging to President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill, General Eisenhower was selected to command the first combined British and American operation for the invasion of North Africa. As the Commander for Operation Torch and the subsequent Operation Husky to invade Sicily, Eisenhower demonstrated his remarkable skill for fostering teamwork among the Allied commanders. This skill for handling the strong personalities of the different commanders and forging them into a cohesive team was the primary factor for his selection as the Supreme Commander for the invasion of France in 1944. No other general, either American or British, with the possible exception of Marshall himself, could effectively lead the coalition. Although Eisenhower’s patience was tested on many occasions, it was his ablitly to build and maintain an effective team that was more important to his success than technical war-fighting skills. He deserves much credit for the final victory in Europe for this leadership ability to forge an effective team which is immeasurably more difficult when your command is a combined Allied force. Although other generals often were getting headlines for the exploits of their units, it was Eisenhower at the helm that made the combined Allied effort effective.

You can read more about Eisenhower’s career both during and after the war at the following link: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/General_Eisenhower